Books v. Rent.

What Books v. Cigarettes Reveals About Postwar Britain.

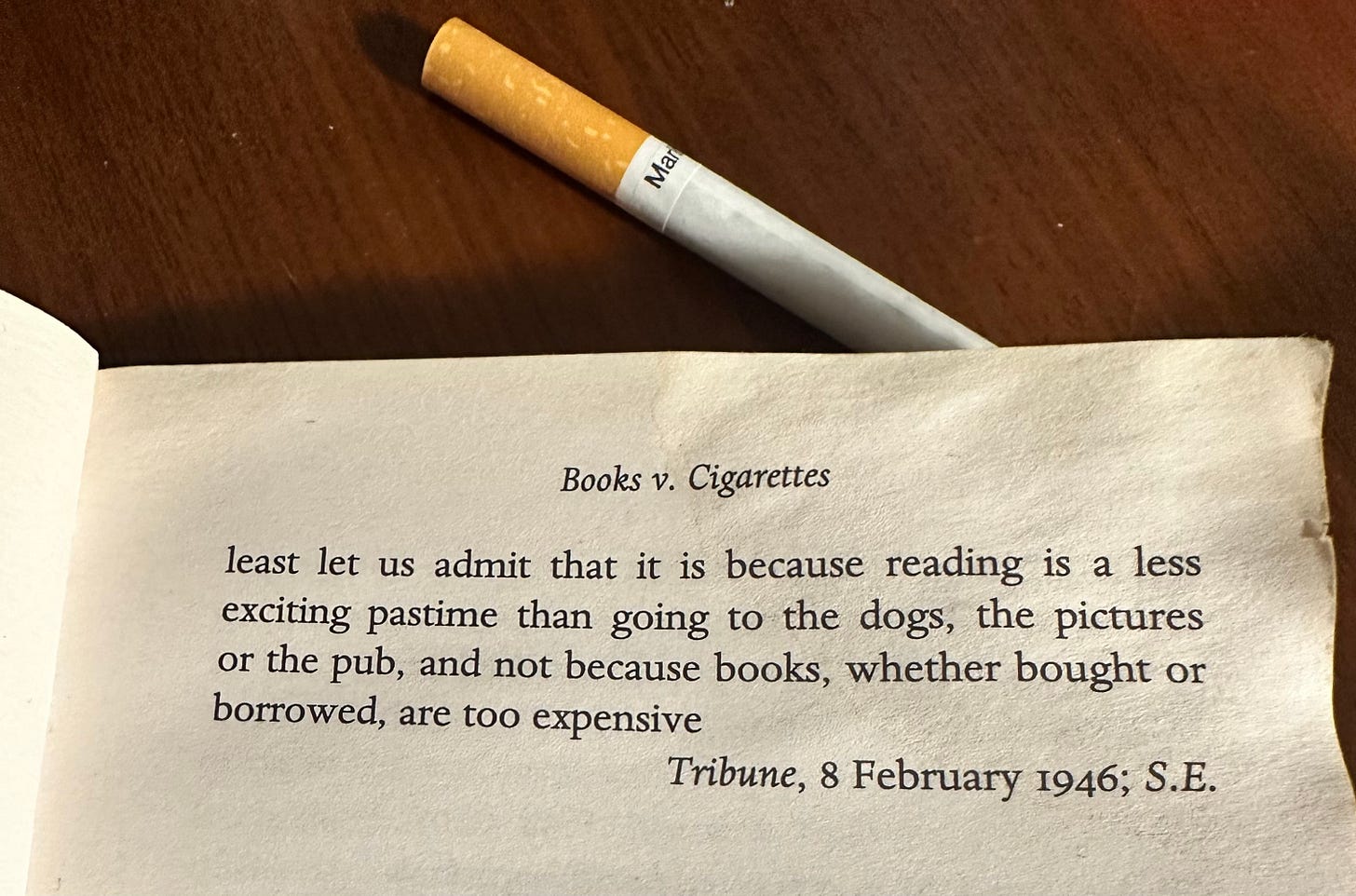

By chance, I happened to pick up a copy of George Orwell’s Books v. Cigarettes this afternoon. For those unfamiliar, it is a short essay in which Orwell compares the cost of books to that of other small luxuries, including alcohol and cigarettes, using his own habits as evidence.

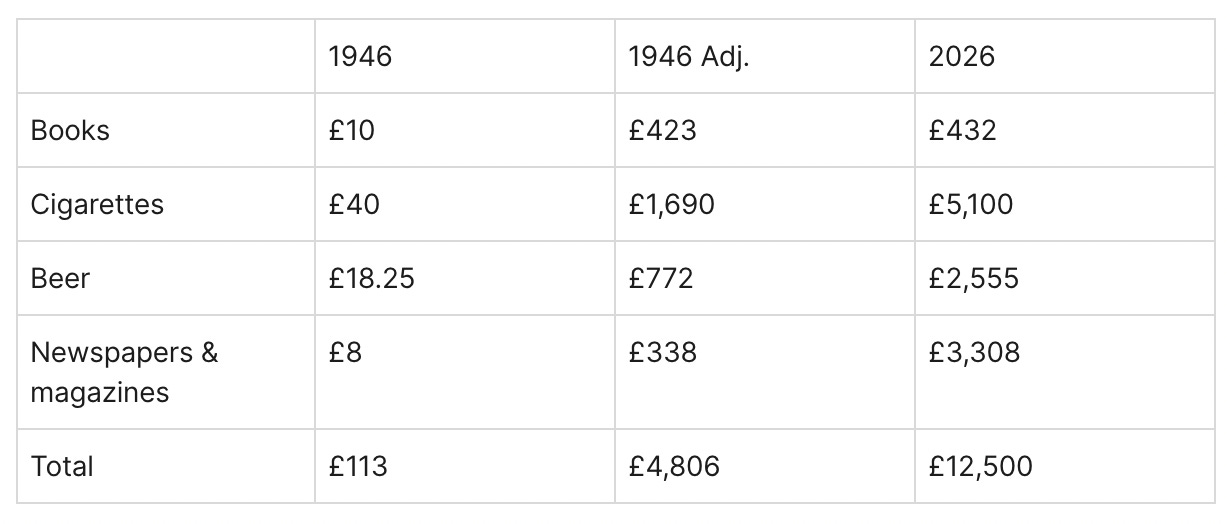

As I read his figures — a lifetime total of £165.15 on books, almost £20 a year on alcohol and roughly twice that again on cigarettes — I wondered how they might look adjusted for inflation, or how my own habits might compare. I’d have left it there had the piece not ended: Tribune, 8 February 1946, SE.

Today is 8 February 2026. A coincidence too neat for Orwell, perhaps — but not one that’s below me.

Orwell bought an average of three books a month (mostly second-hand) and smoked around twenty cigarettes a day (Players). He also accounts for newspapers (two daily papers, one evening paper, two Sunday papers), periodicals (one weekly review and two monthly magazines), and a pint of beer a day.

To spare myself the indignity of pre-decimal coinage, I’ve rounded the figures.

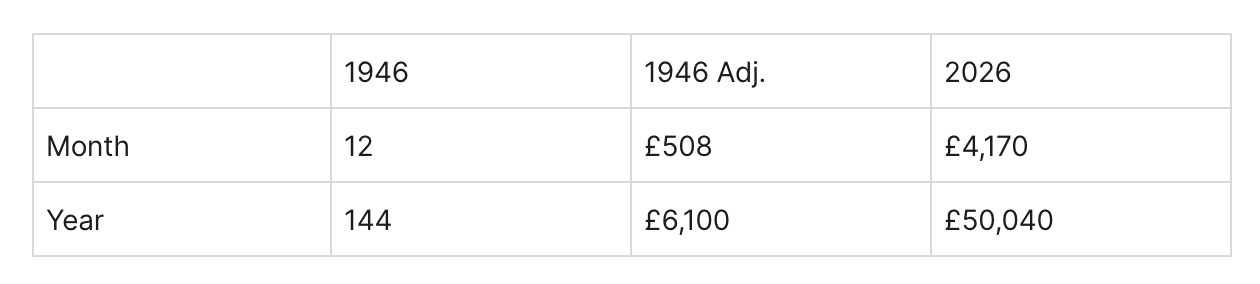

In 1946, George Orwell lived at 27b Canonbury Square, Islington. In his later diaries, he notes that his rent was £12 a month, so I’ll use that figure. The 2026 equivalent is based on The Move Market’s “fair rental market value” estimate.

Orwell doesn’t mention rent in Books v. Cigarettes, but neither would I if I were paying the equivalent of £508 a month for a three-bed flat in Zone 2.

Like much of London in 1946, parts of Islington would have resembled a war zone. But there were still green spaces, good amenities, and strong links to the city. The reason the rent was so agreeable is not that Islington was a bombsite, but that Britain had been subject to rent controls since the First World War — and by the time Orwell lived at Canonbury Square, those controls were not temporary emergency measures but settled policy, backed by popular mandate.

Orwell could afford Canonbury Square on a writer’s income not because writers were better paid, or landlords kinder, but because the state had decided that rent extraction had limits — and that private profit stopped where social stability began.

Rent controls were effectively dismantled in Britain from 1980 onwards, under Thatcher’s government, and rents have risen largely unregulated ever since.

In 2026, it is not the cost of books or cigarettes that makes Orwell’s essay so interesting; it is the unintentional revelation that the author assumes housing is a solved problem.

Substack, 8 February 2026, E.